No matter how we define ourselves, we often lack proof that there are others like us, which can be profoundly lonely. Scariest of all, we may begin to understand what it means to be someone who is set apart in some way: because of complexity, race, disability, or one of the dozen other ways society has decided that people do not wholly fit in.

My pursuits made me an outcast. As a youth, I was fanatically devoted to my clannish Pentecostal religion. Even worse, I was an overly intellectual, introverted, complex child with a wide range of emotions who lacked social skills. I elevated the art of nerdiness to a whole new level. My schoolmates treated me as though I was a total weirdo. Unfortunately, I was self-aware enough to know they were right.

Later in life, my essentials (particularly my sensuality, curiosity, and determination to be free) made me a person who did not fit in. My religious American tribe had no empathy for someone with myriad questions, open sensuality, and a desire to be free from rules. Very few people, if any, tried to understand or befriend me.

I was too scared or religious to retreat into drugs like most of my classmates in the Appalachians, but somehow, I managed to find places to meet a lot of friends. Despite my many moves (over 34 times), I immediately located that communal space in the new area. And I always found friends. It wasn’t at school, a bar, my neighborhood, or a church, although you could call it a cathedral.

That place was libraries.

First was the Old Library Building in Chattanooga, Tennessee, a Carnegie library built in 1904. Then, there was the ancient red brick library at Lee College (now torn down), with its secluded antique reading nooks and ornate wrought iron accents. Other spiritual spaces include the Peabody Library in Baltimore and the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Today, my communal space is the 130-year-old Biblioteca Pública Arús. (Pictured at the beginning of this article.)

And oh, the friends I made. I whitewashed fences with Tom, rafted with Huck, solved mysteries with Frank and Joe, joined Jimmy’s club, got my first crush on Nancy, learned to grok from Valentine, and felt the first quivers of lust for Eunice. I befriended someone eerily like me, Cory Mackenson, a precocious boy in a little southern town who wanted to be a writer. We flew over our neighborhood together and are friends to this day.

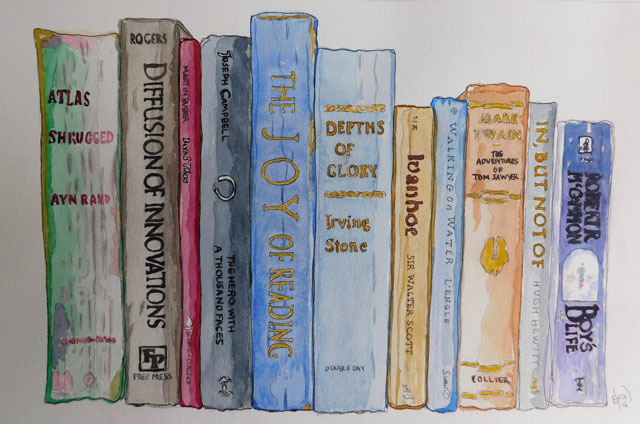

Later, I fell head over heels for Dagny, admired Howard’s principles, and was heartbroken for Rebecca. I met myself again in Pyotr’s simplicity and emotional directness, was continually frustrated with Nicholas, and was awed by Sancho’s common sense and devotion. As I have grown older, my friends have become more gender and race-diverse and certainly more free-thinking. And just last week, my new friend Audre taught me what it means to be black, lesbian, mother, warrior, and poet. All my best friends are from books.

Now, back to the “real” world. The most thunderous sound in life is the thud of a single page as it turns from one chapter to the next.

Every life is organized around several events that divest us from those we thought were true friends.

We spend the years between these episodes benefiting or suffering from their loss until the arrival of the next purging moment. For me, it was constant relocations, questioning religion, a divorce, renouncing my faith, moving to the wilderness, and ultimately, moving abroad. The thousands of people I previously called friends in real life gradually dwindled to a handful and now to a precious few.

There must be a name to the phenomenon that causes human friends not to call, text, video call, or email when you move out of town or out of the country. It takes the phrase “out of sight, out of mind” to a new level.

The four or five human beings who fit my lofty description of a close friend are mostly younger and thus busy with the first half of life. They are human and struggling through the complexities of life, like me. Only one of them has proven a faithful and consistent companion, a best friend through thick and thin, near and far, and fortunately, I am married to her.

After nine months in Barcelona, I have made many new friends and acquaintances, and I am grateful for that. We communicate with a garbled mashup of Spanish, English, Farsi, Chinese, and Italian. We are a diverse group of races, beliefs, genders, sexual preferences, and philosophies. But again, they are all younger and have busy and complex lives. It is a curse and a blessing—I have always attracted younger friends.

I often wonder, isn’t anyone else retired?

However, my best friends have been with me throughout my lifetime of reading. I’ve found others who have similar anxieties, fears, desires, and pleasures. And having seen myself in a friend, albeit in the pages of a beloved book, I’m different—I feel understood and less alone.

If one friend makes you feel a little less alone, imagine tapping into an entire ancestry of them. Yes! There are other Randys, other complex beings with wide-ranging emotions, who are unafraid to say what they think, ask probing questions, openly discuss and break taboos, and create sensual art. Friends like Audre Lorde, Henry Miller, Pauline Réage, Carl Jung, Madeline Miller, and Stephanie Stevens, to name a few. And these friends get me and are never too busy for me.

These friends made me more empathetic to my childhood self; they helped me understand my adult self: my deepest longings, my gender identity, and ultimately, my bildungsroman (my Quest) by focusing on my life from childhood to adulthood and applauding and supporting my moral and emotional development.

As I age, I develop a deep appreciation for old friends, ha, an appreciation for everything old: old books, old libraries, old cities, old countries, and old wine. I’m still an outcast, just older. But my best old friends have helped me understand that that is okay. It is who I am. Through the years, they have held a mirror to my soul. So anytime I get lonely, and there are many, I visit my cathedral of treasured books and have reflection time with my closest friends. Thankfully, because of them, my life has not been a long, dark night of the soul like my fellow Spaniard, Juan de la Cruz; it is more of a tranquil saunter as I enjoy the second half of life with my friends.

Leave a Reply